Advances in treating tooth decay may one day lead to an ability to restore tooth tissue – and to avoid root canals, according to scientists. Shirley Wang and Baylor College of Dentistry Professor of Biomedical Sciences Dr. Rena D'Souza join Lunch Break with details. Photo: Getty Images.

Could the days of the root canal, for decades the symbol of the most excruciating kind of minor surgery, finally be numbered?

Scientists have made advances in treating tooth decay that they hope will let them restore tooth tissue—and avoid the painful dental procedure. Several recent studies have demonstrated in animals that procedures involving tooth stem cells appear to regrow the critical, living tooth tissue known as pulp.

Treatments that prompt the body to regrow its own tissues and organs are known broadly as regenerative medicine. There is significant interest in figuring out how to implement this knowledge to help the many people with cavities and disease that lead to tooth loss.

In the U.S., half of kids have had at least one cavity by the time they are 15 years old and a quarter of adults over the age of 65 have lost all of their teeth, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. An estimated $108 billion was spent on dental services in 2010, including elective and out-of-pocket care, according to the CDC.

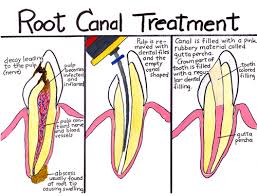

Tooth decay arises when bacteria or infections overwhelm a tooth's natural repair process. If the culprit isn't reduced or eliminated, the damage can continue. If it erodes the hard, outer enamel and penetrates down inside the tooth, the infection eventually can kill the soft pulp tissue inside, prompting the need for either a root canal or removal of the tooth. Pulp is necessary to detecting sensation, including heat, cold and pressure, and contains the stem cells—undifferentiated cells that turn into specialized ones—that can regenerate tooth tissue.

Researchers from South Korea and Japan to the U.S. and United Kingdom have been working on how to coax stem cells into regenerating pulp. The process is still in its early stages, but if successful, it could mean a reduction or even elimination of the need for painful root canals.

While much of the work has shown promise in the lab and in early work in animals, including dogs, there have only been a few reports of experiments in humans.

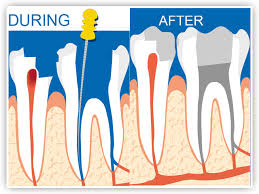

The root-canal procedure involves cleaning out the infected and dead tissue in the root canal of the tooth, disinfecting the area and adding an impermeable seal to try to prevent further infection.

But the seal does not always prevent new infection. While the affected tooth remains in the mouth, it is essentially dead, which could impact functions like chewing. That also means no living nerves remain in the tooth to detect further decay or infection. Infection could subsequently spread to surrounding tissue without detection. An estimated 15.1 million root canals are performed in the U.S. annually, according to a 2005-06 survey by the American Dental Association, the most recent data available.

"The whole concept of going for pulp regeneration is that you will try and retain a vital tooth, a tooth that is alive," says Tony Smith, a professor in oral biology at the University of Birmingham in the U.K. "That means the tooth's natural defense mechanisms will still be there.

"I think we are really just at the opening stages of what is going to be a very exciting time, because we're moving away from traditional root-canal treatments."

Some scientists have focused on growing entirely new teeth. More are focused on trying to grow healthy new pulp inside the hard shell of tooth enamel, either by stimulating or encouraging stem cells or by better controlling the inflammation that goes on in the mouth in response to an infection.

Some of the challenges with making new teeth are generating not just the right tissue but also the right structure, as well as how to place the tooth or the new pulp in the mouth, according to Rena D'Souza, a professor of biomedical sciences at Baylor College of Dentistry. Beyond anti-inflammatory medication, options for tackling the infection while the new treatments work are limited. And, as with stem-cell research efforts with other body parts, successfully regenerating dental tissue in the lab or another animal doesn't mean it will work in a human body.

Dental stem cells can be harvested from the pulp tissue of the wisdom and other types of adult teeth, or baby teeth. They can produce both the hard tissues needed by the tooth, like bone, and soft tissues like the pulp, says Dr. D'Souza, a former president of the American Association for Dental Research who will become the dean of the University of Utah's School of Dental Medicine Aug. 1.

She and colleagues at Baylor and Rice University focused on regrowing pulp using a small protein hydrogel. The gelatin-like substance is injected into the tooth and serves as a base into which pulp cells, blood vessels and nerves grow.

In a study published in November, they were able to demonstrate pulp regeneration in human teeth in a lab. They will soon be testing hydrogel on live dogs. In addition, they are looking at the potential of the hydrogel to calm dental inflammation.

The hope with pulp regeneration is to improve the health of the tooth while minimizing the pain often associated with current treatments like the root canal—although under some circumstances a date with a drill will still be necessary, experts say.

Another approach is to extract pulp from teeth and separate out the stem cells, then transplant the stem cells with molecules that encourage their growth back into the tooth cavity. Research published last month by Japanese researchers on dog teeth showed this method appeared to be effective in stimulating the tissue around the transplanted cells to produce pulp tissue. The study was published in the journal Stem Cells Translational Medicine.

Researchers are also focused on understanding how dental stem cells usually get the message from the tooth about when to regenerate pulp.

Dentin, a hard tissue that protects the pulp, is one critical element. When bacteria break it down, it releases molecules that stimulate the regeneration of tooth cells. The University of Birmingham's Dr. Smith and his team have identified a number of chemicals that transmit these signals and are working on figuring out a way to release these messengers therapeutically as another way to repair teeth.

At the University of Cardiff in Wales, Alastair Sloan, a professor of bone biology and tissue engineering at the School of Dentistry, is examining how the use of materials currently used to treat tooth decay may be able to prompt dentin to release additional proteins to aid growth.

Dr. D'Souza estimates that human clinical trials of the hydrogel strategy could begin as soon as two or three years from now and be available as a therapy within five years. Other researchers working on different methods estimate that human trials may take place within the decade.

Progress with regenerating other types of tooth tissue may mean the end of fillings one day as well. While pulp is used as a lining material to protect the crown and roots of the teeth, other researchers are studying whether other biological materials could be generated to withstand the mechanical forces that come from chewing and other functions.

None of these advanced techniques negate the need for simple hygiene. Brushing and flossing are always important, and not just for oral health, according to experts.

"If you have a healthy mouth it's indicative of a healthy body and vice versa," Dr. D'Souza says.